VISITING THE GALAPAGOS - Introduction

Take a step towards the extraordinary!

A brief history

The Galapagos Archipelago was discovered by accident in 1535 by Tomás de Berlanga the first Bishop of Panama, who drifted off course whilst sailing from Panama to Peru. The islands didn’t appear on maps until the 1560-1570s, when they were noted for their tortoises - probably as a signpost to mariners who right through until the 19th century ate them during long sea journeys. The first charts of the archipelago were made by buccaneers in the late 17th century. Scientific exploration began in the late 18th century.

Ecuador claimed the Galapagos in 1832, when General José de Villamil was named the first governor, he was placed in charge of a single colony of ex rebel soldiers on Floreana. Charles Darwin’s now famous visit occurred just a few years later, in 1835. The islands were inhabited by only a few settlers and were used as a base for penal colonies, the last of which, on Isla Isabela, was closed in 1959.

Some of the islands were declared wildlife sanctuaries in 1934, and 97% of the archipelago officially became a national park in 1959.

The Charles Darwin Research Station on Isla Santa Cruz began operating in 1964 and the Galapagos National Park Service was formed in 1968. Tour boats began to visit the in 1969 and, by the mid 1980s, tens of thousands of people from every nation were coming each year. In 1986 the Ecuadorian Government formed the Marine Resource Reserve and in 2001 the Galapagos Reserve was declared a World Heritage Site.

To many people, the Galapagos Islands are imagined as a far-off mythical land, where giant tortoises struggle across barren inaccessible hillsides and sea lions playfully nip marine iguanas as they dive for their lunch. The reality is that you can visit the Galapagos to witness the amazing animals and the fabulous surroundings that they inhabit. Today, Charles Darwin’s famous comment about the island, seems so unfitting:

‘Nothing could be less inviting than the first appearance. A broken field of black basaltic lava, thrown into the most rugged waves, and crossed by great fissures, is everywhere covered by stunted, sunburnt brushwood, which shows little signs of life’. (C Darwin, 1845)

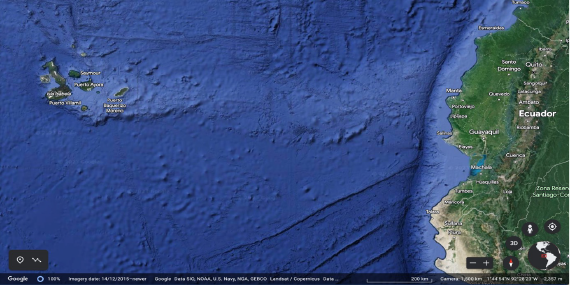

Our location

The Galapagos Islands are located in the Pacific Ocean, almost 1000 km west of mainland Ecuador, the home nation of the archipelago. Here are found 13 large islands, 6 smaller islands and 107 islets and rocks scattered across the open ocean.

The archipelago is located on the Nazca tectonic plate, adjacent to the Galápagos ‘hotspot’, this is to the west side of the area, where the Earth’s crust is being ‘melted’ from below, by a mantle plume creating volcanoes.

The first islands that were formed here, many millions of years ago, have already drifted east from the hotspot, have been eroded, and have disappeared beneath the sea. In contrast, the two youngest of the extant islands, Fernandina and Isabela, are still being formed and it will be many more millions of years before they are eventually located to the west side of the archipelago and eroded down to the point where they too disappear beneath the water.

Most of the extant islands represent the summits of once active volcanos, some of which have risen over 3,000 meters from the Pacific floor. On Isabella, the largest landmass, it is particularly easy to see how volcanoes are still shaping the island.

Darwin Island forms the north most point of the archipelago, San Cristobal Island the east most, Española Island the south most, and Fernandina Island the west most. Wolf volcano on Isabela Island, at approx. 5,800 km2, forms the highest point in the Galapagos, rising some 1,707 m above sea level.

A bit about evolution

The Galapagos archipelago is so far removed from the main continental landmasses that its climate is largely determined by the complex pattern of ocean currents that sweep around it, driven by the trade winds.

The relative isolation, the climate, and the ongoing seismic and volcanic activity have together caused an unusual and totally unique set of animals to evolve. These include the marine iguanas, giant tortoises (after whom the islands are named), the most northerly species of penguin in the world, flightless cormorants, giant cacti and multiple subspecies of mockingbirds and finches. Fortunately, for visitors, the ecosystems of the Galapagos remain remarkably unchanged, with an amazing 95% of pre-human biodiversity still intact.

It’s an amazing fact, the Galapagos is still the second most pristine place in the world, after Antarctica. This means that you can still see, today, what inspired Darwin to write his theory of evolution after his visit in 1835.

Who lives where on the islands…

The five inhabited islands are Isabela, with the largest landmass, Santa Cruz, which is by far the most populous island, Floreana, which retains the smallest population (some 200 people), Baltra, located just north of Santa Cruz, which houses an airport, tourism dock, fuel containment, and military base, and San Cristobal, home to the capital of the islands and its second largest airport.

Travel from the mainland to the Islands

There are currently several passenger airlines operating from the mainland to the Galapagos, the main carriers being Avianca, Latam and Equair. Services are provided from both Quito and Guayaquil airports. It is sometimes possible to obtain a seat at the airport on the day of departure, but to avoid disappointment it is best to make a reservation ahead of your journey.

Ticket pricing between airlines does not vary much and the cost is high, but this is the way things are at present, as there is currently no practical alternative to air travel.

There are two airports in Galapagos that handle flights to and from the mainland. A relatively small one on San Cristobal Island and the main airport (referenced above) located just to the north of Santa Cruz Island, on Baltra Island.

If you are using San Cristobal’s airport you are just minutes from the island’s main town, but those arriving in Baltra have to take a bus to the island’s dock and, from there, a ferry across the narrow ‘Itabaca Channel’ separating Baltra from the northern tip of Santa Cruz Island. Once passengers disembark the ferry, they then have to travel south across Santa Cruz to their destination – most often the town of Puerto Ayora, a 45-to-60-minute ride by taxi or bus.

Intra-island boat travel

There are once or twice daily passenger ferries (small powerful motorboats) that travel between the main populated islands, Santa Cruz, Isabela, San Cristobal, and Floreana.

Journeys typically take about two hours each way but, between July and December, the sea can be choppier and journeys a little longer. In this season sea sickness tablets are popular with travellers.

Morning ferries servicing Santa Cruz, Isabela, and San Cristobal generally depart between 06.00 and 07.00 hrs. Afternoon boats between 14.30 and 15.00 hrs. Floreana is connected by a once daily service leaving Santa Cruz at 14.30 hrs. Fares are generally $25-30 per person per trip. Note: You will also pay a small fee per person for your dock-to-ferry and ferry-to-dock transfers.

Intra-island air travel

There are small passenger planes that regularly fly between Baltra, Isabela and San Cristobal, at a cost of approx. $170 per leg. Although expensive, those who suffer from sea sickness might find this a more comfortable way to travel, especially in the colder season when the ocean is rough.

-

For details of the entry requirements to visit the Galapagos, see Plan your trip

For information about seasonal condtions, see Climate and dive conditions

For a list of useful things to bring on your trip, see Packing list